Jaffna in the postwar context remains a troubled space. Yes indeed, there is no longer an embargo, and one can take the train, bus or fly easily. Yes, there are new super markets and people can walk around more freely. However, the scenario of domination and oppression continues in other ways. During a recent visit, forms of violence and domination were clear not only in the large number of Navy and military camps still there, in the ways they have become permanent installations in the North, but also in the ways in which new forms of postwar Buddhism and Tourism function with close ties the military apparatus. The first example is the Sangamitta Buddhist Temple built in Madagal at Dambakola Patuna in 2009, right by a Navy camp. Here, new histories are produced to penetrate the North as belonging to Buddhists. If Tamils have claimed the Jaffna Peninsula as the traditional homeland for Tamils, then erecting temples such as this is a way of rebutting this claim. The second example is the Hammenhiel Resort, a Dutch forte now run by the Navy for profit. In both locations, the local populations have been either evicted from those spaces, or are not allowed to fish in those seas, while the military-Buddhist-tourist complex functions to serve the South.

Sangamitta Temple: the Invention of Tradition and History

The Sangamitta Temple was built and opened in 2009 in the postwar period. Despite the devastating end of the war, the Navy and the state did not hesitate to construct the temple and claim it as a Sinhala Buddhistspace. One would imagine that the end of war would have drawn the state’s attention to more urgent matters such as humanitarian assistance for Tamil civilians killed in the Vanni. However, the Sangamitta temple was built immediately after the war, close to an enormous Navy base because supposedly Sangamitta landed there (approximately 250 BC) bringing with her a Boe sapling. The sapling is said to be the same as the one found in Anuradhapura today. While this area is not a High Security Zone, it might as well be, as the Navy dominates the landscape. The proximity of the Navy camp and the temple locate how Sinhala Buddhism and militarism are integrated formations.

The creation of a temple here is part of an invention of tradition done in the Tamil heartland so that Sinhala Buddhism can claim a place for itself there, even though no Buddhists live in the area, and no temple existed there until 2009. There are two large statues of Sangamitta: one inside the temple and the other just outside by a lake. These large statues claim: Buddhism entered the country from this point and so the North too belongs to the Buddhists.

There are two other additional claims that tell us about colonial penetration into Tamil areas. One is that the temple was opened by Shirani Rajapaksa, as if she is the modern day Sangamitta or a continuation of Buddhism in modern form. She places herself as the continuation of an ancient lineage, a formation that Joseph Roach has called “surrogation,” in his work The Cities of the Dead. The second is that the military’s claim that this temple was made possible because brave military personnel defeated a terrorist threat. So, there are signs celebrating military victory and prowess. Here, the trauma of the final war, and the suffering of Tamils in the North at the hands of the state and the Tamil Tigers are erased and retold as a glorious victory for Buddhism. The overall message of the signs and the temple is loud and clear: this land belongs to Buddhists, and the military is here to stay.

Tourism and the Military Complex: Hammenhiel

I have already written about how tourism in Passikudah is a means of domination because of how the tourist industry is displacing Tamil fishermen and destroying the environment. We see a more direct example of this in Hemmenhiel Forte.

The Forte is found in a tiny island off of Karainagar, and was built by the Portuguese, then fortified by the Dutch after 1658, and then became a prison under the British. In Postcolonial Sri Lanka, the Forte continued to be used as a prison. Indeed in 1970/71, Rohana Wijeweera was briefly imprisoned there when it was rumored that he was going to be rescued from Jaffna prison by students at Jaffna University. His writings on the wall are still there.

Since 2012, this prison has been converted into a luxury hotel, albeit with only four fancy rooms. Again, the resort is just beside a Navy camp, and as my young navy tour-guide told me, “we do not let locals anywhere close by. No local fishermen are allowed into these seas.” The sea is beautiful and pristine, bot not to be used by local Tamils. It is meant for tourists and the elite, for a full-board room costs Rs. 20,000. Even entering it is difficult for the path that leads to the restaurant in the peninsula and to the resort is through the Navy camp entrance. So, I had to stop and get permission even to go in. Without prior permission and organizing, the public cannot simply go to the island.

We can ask how the restricted access is legal to a site that is a historical site, and paid for and maintained through public funds. How is restricting access possible when the salaries of the navy officers who run the resort are paid by the state? Furthermore, we can also ask about the ethics of a military transforming itself into a capitalist business, running hotels like this, and making profit. Where do these profits go?

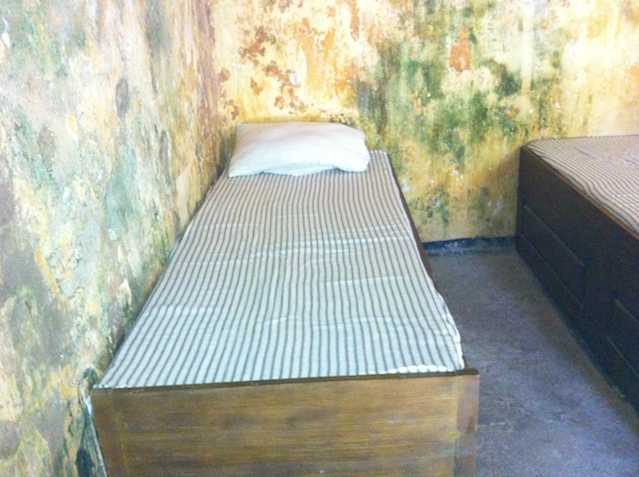

What is perhaps most astounding about the Hemmenhiel Resort is not, however, the fact that the hotel is an articulation of the postwar military-tourist complex, but also the hotel’s making pleasurable that which was traumatic for Tamils in the North. One prison cell has been transformed to create a tourist experience of prison life. For if you pay Rs. 6,000 or US$ 50, you can “experience” what it is like to be a prisoner by living in a cell instead of one of the fancy air-conditioned rooms. You can simulate the pleasures of prison life, you can use a renovated prison bathroom, can wear a prison uniform, and will be served from a metal plate and cup. What is most horrifying about this experience is that it transforms something that has been traumatic for so many Tamils in the North, mass incarceration, torture, and violence into some kind of “fun experience” for the rich. When I listened to my young guide explain how you could experience being in prison, I was reminded of how many young men and women languished in prison during the war with no opportunities for bail or a court hearing under the PTA. I was reminded also of the terrible killings of Tamils during the 1983 pogrom in Welikada prison. All this trauma is erased as the navy turns a history of violence into a history of fun. Similar kinds of exploitation of poverty can be found in The Emoya Luxury Hotel and Spa near Bloemfontein, South Africa, which offers tourists a Shanty Town experience for a cost. Similarly, if you want to pretend to be a prisoner for a day, you can pay for it and have fun at the same time at Hemmenhiel Resort.

These examples are only two of so many instances of postwar violence perpetuated upon people in the North. The North remains occupied and militarized. Southern state violence continues to impose itself, not only directly through the gun, but through other forms of coercion. Local populations are denied access to lands, to resources and to their homelands by a state that is intent on claiming the North as part of their Buddhist-Military-Capitalist right.